Interview: Frederike Doffin & Cameron Middleton

Title of Art Video from Thesis Performance: “Transitional Momentum for Ecological Grief”

Cameron: We wanted to have someone speak from the Movement, Mind and Ecology Masters but I particularly wanted to talk to you because we used to be neighbours, and I saw you developing the ideas for your thesis over time. Can you tell me more about how you came to the idea of transitioning ecological grief through the body?

Frederike: Um, yes, actually, I think the fact that I worked with grief was because I felt a need in my own body to process grief. I have the feeling it’s part of my own healing journey, that I felt a need to commit to work with grief in parallel. And I think in the whole project, there’s something where the personal and the collective are coming together. The personal grief and planetary grief is very strong in these times because we experience so many losses on a collective level through ecosystems collapsing and wars again expanding. So I felt the need to address the grief I could feel in my gut biome, but also in the collective field. So I wondered how we could develop practices that are nonverbal, through the body? And when I started this, I felt there was actually a lot of support. And the support came for me mostly from the plant realm, maybe also because I’m a gardener. I’m not trained as a gardener, but I’m always gardening. We have a big garden in Berlin, and it’s something I’ve always been doing. And also sharing this, actually, I feel this project, ‘transitional momentum for ecological grief’ is the continuation of a research project that I did last year for which I received funding for half a year. I did research that was called relational practices of bodies and land and I was comparing our way of relating from dance to gardening. And at the end of this practice, I realized that because there was the drought, and especially in Europe it was very, very hot.

Oh, yes, the drought.

So I realized how much we were struggling in our garden collective. And we had a lot of conversations about water, how to deal with water. And we were very busy with the vegetables. And then one day we realized that actually one of the largest trees in our garden, a big pine tree, was about to die. The groundwater was sinking so that the tree’s roots could not reach the groundwater anymore. I felt such a sense of loss, that this huge pine tree is going to die while I had just been busy with the small vegetables because we needed to eat. And then realizing that this tree is dying. I felt that. I felt that my nervous system was in a state of fight or flight towards climate change, that I wanted to resist the change that was happening. I had a kind of personal collapse.

Did you find any sense of relief from that during this time?

Yes, well, I was crying a lot when I saw that this tree was dying. And I had the feeling that my nervous system was actually releasing. So then I was wondering what happens if actually we go on the level of the nervous system, we start to surrender instead of resisting change. And I think what happens when we recognise climate transition, is that we can induce positive change, but I feel there’s a point where we need to surrender. And for me that’s when I came in contact with grief because I feel this grief is part of this surrendering process.

Yeah, that’s very powerful. I really resonate, and I really appreciate you also having the clarity and the wisdom to be able to be both in those powerful emotions, but also to be able to step outside into the broader experience of where your process is like a microcosm of the whole. Because grief really can take us into an abyss. So now as I think about your thesis presentation in your work, you focused on this beautiful large pine tree in front of the old postern building. Can you say more about that and how you set up your installation at the Postern to help people move through ecological grief?

So I feel the project started much earlier. I don’t know if the project started when I was like two or three years old, when I experienced a significant loss, or with a pine tree one year ago in my garden. But then this creation process started three months ago where I felt like, okay, I have all this research and these different experiences, and how could it now materialize and come into form for some kind of workshop format or a facilitated space where I invite other people? I was trying to figure out where was going to take place and who would be my collaborators. And then I was on the train back from Berlin to Devon, and I closed my eyes and asked, who are my collaborators? And then I saw this pine tree in front of the old Postern that somehow it’s very present because it’s very tall, but it’s also a tree where I just always walk by and I didn’t really recognize it. So it was a very intuitive way of asking for support and receiving it. And I think this was very much part also of the facilitation to work with imagination as a creative faculty, using visualizations and intuitive ways of knowledge making.

There is a unique pedagogy that has been developed at Schumacher of somatic work, experiential learning, place-based learning. How important was learning to you? You mentioned intuitive ways of knowing. Can you say more about that, what that means?

I think I learned the most from plants during those nine months and from my classmates. So I feel I was really recognizing nature as a teacher. And I think also at times when I was a bit frustrated with our course, it really helped me to shift perspective that what I’m learning here is much more than the course or how it is structured, or who the people are who are holding the lectures. I also think that our own bodies are our biggest teachers. I think especially in trauma work or work that is connected to healing processes, we need to provide a space where we can listen to our body. I feel like nature and the body are teachers.

And you were asking me about pedagogy?

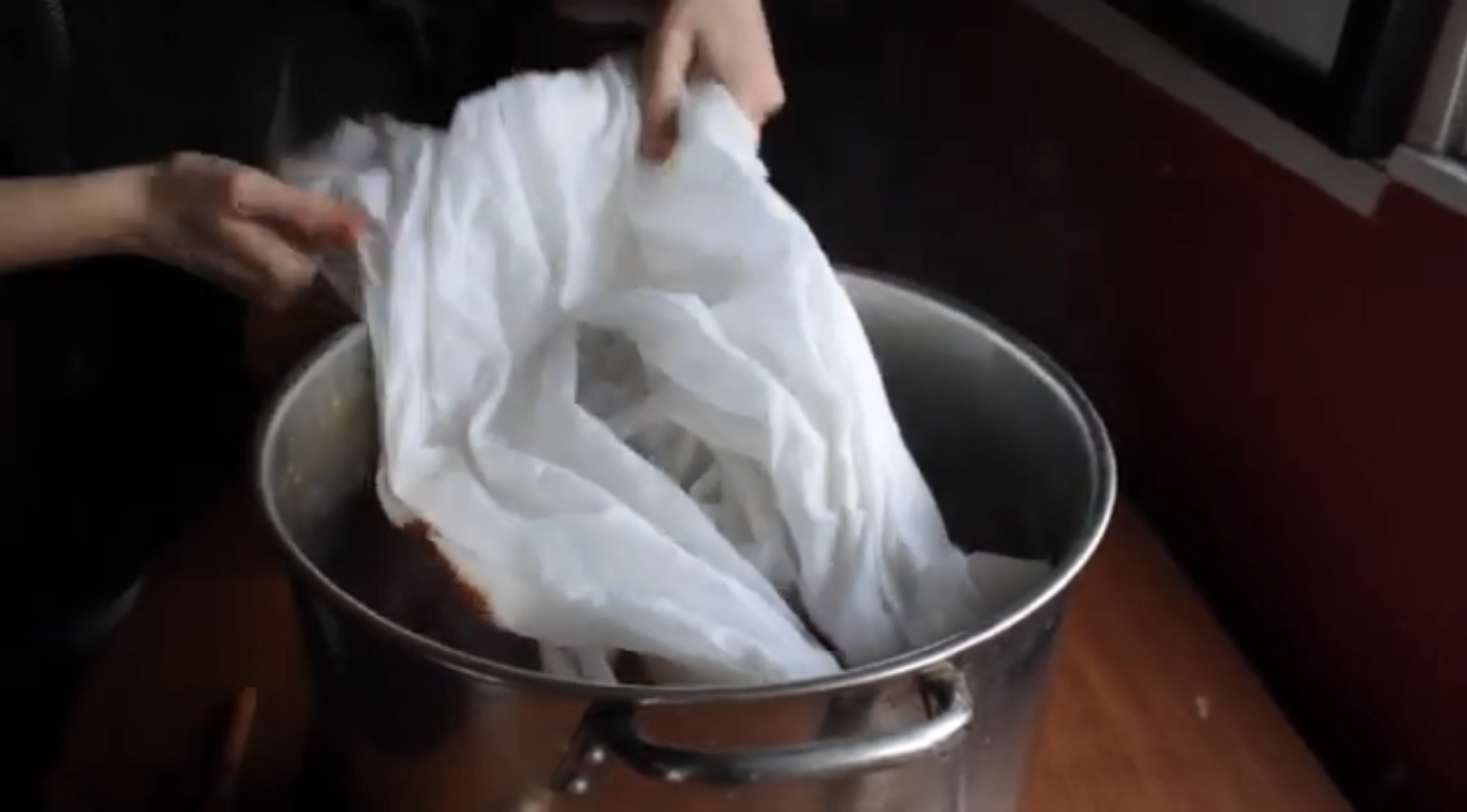

Yes I was wondering if you were interested in finding ways to extend this type of body-centered learning with others as a new pedagogy. For example, could we talk about your onion fabric installation? I was deeply moved by that on multiple levels. The way that onion skins were used and then the way that the fabric wrapped around so that I could feel safe and health and that I could cry. And the prompt or the offering in the booklet was about women getting together after the trauma of World War II to cut onions and cry. Can you say more about that?

It’s actually a story that is more fictional, but it’s also told as a story, and it could have happened this way. Maybe it even did happen. In Germany, we have a lot of guilt and shame still in our family lineages, and people just didn’t speak about their grief and relation to the war. So there’s a book by Gunter Grass where he’s writing about these meetings of people gathering and cutting onions together.

I think in the workshops themselves I see myself more as a facilitator or curator of the space, like a space-holder. And I think what I would love to develop further is maybe this co-learning through tending with the memory cards, for example when we had verbal grief. I think there’s something that happens through empathy. If somebody shares something, I resonate with it and it’s already healing something in myself. So this is how actually there can be some agency to the group and the group starts to hold space for each other. So I think in the future I would love to emphasize this even more. And having these plant companions, that each person was on a journey and really not feeling alone in whatever processes they are in with grief or exploring love or joy. And also this is like getting inspired from each other. And I would love to consider these workshops also as a toolbox, that other people can take this toolbox and share it somewhere else, maybe with honoring or quoting the work, but that it could become like a toolbox that can travel. I think this is something I learned in Schumacher College, how we bounce ideas around and that people are not that precious about their authorship.

In the art scene or in the dance scene in Europe, there can be competition and because of the lack of funding possibilities which can make people less generous about sharing their ideas. And this is something I really appreciate here, that people are like, please take my song and sing it somewhere else.

Like the way that the plants do. But you’ve just offered a segue into my next question, which is what your journey has been, your education, that led you to Schumacher. I would love to hear how you became a dancer and then how that led you into this place.

Yeah, that’s very simple but also a big question. I started dancing really early and I didn’t intend to make it a profession, but I think I just always continued dancing, it was a way of expressing myself. There were also points in my life where I wasn’t really trusting language as an expression and where I think I was always coming back to movement or body language as something that I trusted more. But I wouldn’t only define myself as a dancer. I think being a shiatsu practitioner became really important.

And I experienced great healing from the shiatsu session that you gave to me. And actually today, in honor of that, if I just may say, I have a little plant companion, which I don’t know if you can see, is a piece of Greek basil that was smelling so incredible. And it seems like it’s providing even more of its beautiful scent cloud now that we’re talking about it.

Basil is such a great plant. We should read more about basil. I think basil is quite a sacred plant.

And on that note, I would love to hear more about how plants and gardening influenced your journey to Schumacher.

I was always gardening. But before I didn’t consciously link dancing and gardening. It’s only last year that I started to realize how much my gardening is informing my dancing and art making. Yeah. And yeah, it was through a friend that I heard about someone studying holistic sciences here. And then it was still quite a journey. It took me like two and a half years to get here to raise the necessary funds and find ways with the visa. I think you understand this as we are both international students.

Yes, for me coming to school here became like a pilgrimage destination that was part of a complex journey to make it happen.

And a funny thing happened was just a few days before I left to England, I was in my garden in Berlin. And there’s a little cottage in the garden where other people have also been before gardening. And I just pulled out a paper because I needed a piece of paper to make a little note. And then the paper was a seed bill from Dartington. Like, someone in my garden in Berlin, like, I think seven years ago, had ordered seeds from this area here in Dartington. And I was realizing, oh, my God, there were seeds from this area in darting that were sown in my garden in Berlin. Yeah, I think the plants were still there. It was like herbal plants. I think it was oregano. Then I was like, okay, I think I really meant to. And I also realized how places are connected through plants.

Stills from film of Frederike’s MME Thesis by photographer/filmmaker Kylan Casey

Frederike’s onion fabric installation was a reference to Gunter Grasse’s storytelling imagining a community’s response to addressing unspeakable grief in his work, Die Blechtrommel.